Tracking Down the Stanley Park Pictograph Rock

I’m often asked about how busy I am, what events I’m attending, and which trips I’m taking next all for the sake of my blog. It seems like a pretty glamorous life but honestly I am most happy when I can sit at home my desk with a hot cup of coffee, look out at the rain that’s pelting Downtown Vancouver, and sift through 100 year old photos to track down a unique story. That happened to me yesterday when I was searching the City of Vancouver Archives for random holiday photos and I came across “Pictograph Rock“. Never before had I seen this large boulder, behind a knee-high fence in Stanley Park complete with a plaque. I immediately began to dig around to find out what this rock was and where it ended up.

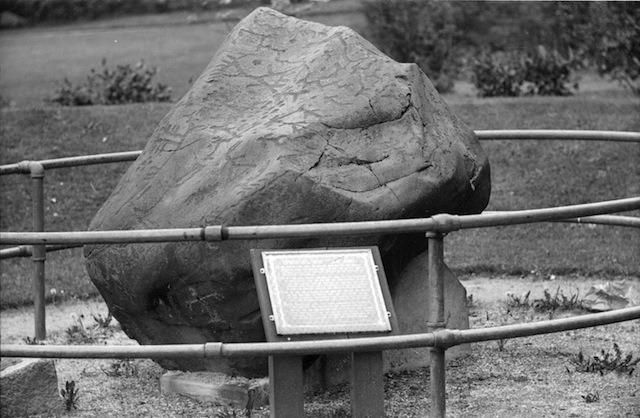

1930: “Pictograph rock in Stanley Park”. Photo by James Crookall. Archives# CVA 260-228.

Tracking Down the Stanley Park Pictograph Rock

After finding a few more photos in the City of Vancouver Archives dating back to the late 1920s, my next stop was a general Google search with the term “Pictograph Rock Stanley Park” which came back with several results about a petroglyph in Stanley Park.

Pictographs and Petroglyphs: “Rock art is generally divided in two categories: carving sites (petroglyphs) and paintings sites (pictographs). Pictographs are paintings that were made by applying red ochre or, less commonly, black, white or yellow dye. Although the majority of the images were traced with the finger, some could be executed with brushes made of animal or vegetal fibres. Petroglyphs are carvings that are incised, abraded or ground by means of stone tools upon cliff walls, boulders and flat bedrock surfaces.” [Source]

It was obvious that this stone and its ancient markings were extremely significant. So why was it fenced off like a curiosity in an exhibition at Stanley Park and how did it get there?

1928: “Pictograph rock from Lone Cabin Creek” in Stanley Park. Archives# Mon P79.1.

Once it was determined that this was a petroglyph, I had more success with search results and was able to put together a timeline for this thanks to the author of the Northwest Coast Archeology blog.

In 1923 the boulder was discovered in the Lone Cabin Creek area of the middle Fraser River, just south of the Gang Ranch. It was then removed (without permission) and moved to Stanley Park in 1926 and positioned near the site of Lumberman’s Arch.

There’s a big gap between the photo from 1930 and then records that it moved to the Museum of Vancouver in 1992, but I would assumed it stayed in Stanley Park until that time. Another website, Spokane Outdoors shed some light on the story. It appears this written between 1992 and 2002, while the petroglyph was at Museum of Vancouver.

The Shelly Stone

“This petroglyph was carved in the vicinity of Lone Cabin Creek, north of Lillooet, on the Fraser River. It first gained Euro-Canadian attention in 1923 upon its discovery by H.S. Brown a cariboo prospector. He brought its existance to the attention of William Shelly, the Vancouver Parks Board commissioner of the era. Shelly proposed moving the six-ton rock from its location on the Fraser to a new home in Stanley Park.

Three years alter, the move commenced. The rock was first loaded onto a raft to be floated to the nearest railway station. This awkward plan failed as the weight of the boulder caused the raft to sink immediately after loading. The next, more successful attempt involved a team of ten horses and a sled. In the dead of winter, the “Shelly Stone” was dragged to the closest rail line. This whole procedure took over a month and cost Shelly two thousand dollars which was a lot of money at the time.

The Shelly Stone arrived safely at Stanley Park. It was set in a foundation of concrete as it was felt this would prevent the enormous rock from being carried off or destroyed. The rock remained at Brockton Pt mislabeled as an Indian Pictograph until moved to the Vancouver Museum basement in June of 1992.”

From the Museum to Repatriation

Naturally my next step was to inquire with the Museum of Vancouver (“MOV”) and it took the team less than a day to get back to me with a very happy ending to the boulder’s story.

“I discovered that we repatriated the petroglyph rock back to Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nations in 2012,” Myles Constable of the MOV told me. He also sent me a link to the MOV’s own blog post from 2012 written by Joan Seidl:

For many years, I squinted at murky black and white photographs taken in 1926 showing a great petroglyph-covered rock as it was hauled away from the Fraser River somewhere in the interior. I despaired that we would ever know the rock’s original location with any certainty. It seemed that removing the rock back in 1926 had been utter folly. It felt against nature to even consider hauling a six ton rock from the interior of BC and move it to Vancouver. But driven by compulsion and arrogance (to my understanding), people did it, and the great rock now sits at the Museum of Vancouver after many years in Stanley Park.

The blog post confirms some of the story from the Spokane Outdoors website (referenced above) about how it was discovered by gold prospector H.S. Brown and moved to Vancouver.

Brown was an admirer of the Mohawk poet Pauline Johnson who was buried in Stanley Park after her death in 1913. His original plan was to sell his placer gold claim and use the proceeds to place the stone by her grave in Stanley Park. When Brown was unable to sell his claim, the chair of the Vancouver Park Board, W.C. Shelly, stepped in.

Shelly wanted the petroglyph in order to add it to the collection of totems poles, house posts, and other First Nations art that he was assembling from throughout BC in order to create a faux “Indian Village” in Stanley Park. (Shelly was apparently indifferent to the fact that the government was trying to evict the real Coast Salish settlements in the Park at the time).

There the boulder sat in Stanley Park, for decades. Increasing incidents of vandalism led the Park Board to ask the Museum to look after the rock in the early 1990s. In 1992, the petroglyph was moved from Stanley Park to the Museum’s interior courtyard. For 20 years, the boulder stood in the courtyard with its many petroglyphs slowly disappearing under a layer of moss and lichen.

The Power is in the Place as Well as the Rock

Photo: Museum of Vancouver, cleaning the stone.

Photo: Museum of Vancouver, cleaning the stone.In 2010, Bruce Miller, an anthropology professor at UBC who also chairs MOV’s Collections Committee, brought the petroglyph to the attention of the Committee.

Bruce explained the contemporary understanding of petroglyphs as highly sacred objects that are integral to their original sites (the power is in the place as well as the rock), and encouraged MOV to work towards repatriation. Bruce brought in archaeologist Chris Arnett who specializes in BC petroglyphs. We shared the documentation we had with Chris. After researching, Chris advised us that we ought to speak with the Canoe Creek Indian Band, now known as Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation, from whose territory the petroglyph had been taken without permission in 1926.

In September 2010 Chief Hank Adam and Phyllis Webstad of the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation visited the MOV to see the petroglyph and meet with our staff. In October, the First Nation formally requested repatriation. After working through the process required by MOV’s Collections Policy, the MOV’s Board of Directors voted to repatriate the petroglyph in March 2011 — lightning speed in the Museum business.

Joan Seidl’s blog post for the MOV is very moving, which is why I have quoted so much of it here. I especially love this passage:

In late August 2011, Chief Adam led us to the exact spot where the rock had stood. It was a powerful experience — the Fraser rushing by, the sun beating down, velvety hills all around. Even the skeptics among us (me) were convinced when we held up the historical photographs of the petroglyph move in 1926 and matched up the silhouettes of the mountains, ridge for ridge. And then, standing there, Chief Adam said, “Look down”. At our feet were more rocks with petroglyphs — as the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation say, “sister rocks”. This was the place.

On June 13, 2012 — 86 years after it was taken — the stone was returned to its original location.

I cannot type any words more appropriate than Joan Seidl’s witness account but it filled my heart with joy to know that this rock made it back to Lone Cabin Creek.

What started out as a random find in the City Archives database turned into the discovery of a bigger message, one I had to take a small journey (albeit around the city and the web) to realize. While many of us wander and travel, there will always be no place like home. The environment, the people, the entire feeling of being somewhere you are comfortable and where you belong – and your own effect on those people and those places can be felt.

I think Joan Seidl relayed Bruce Miller’s message the best by saying: “The power is in the place as well as the rock“. That can apply to many things in our daily lives, no matter how long it takes us to find that special place, or how long it takes us to reach home again.

4 Comments — Comments Are Closed

As much as I’m loving travelling and experiencing new things I always love the feeling I get when I come home.

Great story! I have lived here 30 years and never knew of this.

Wonderful to hear the story of an archeological theft being rectified. For too long the important religious objects of many societies have been stolen as curiosities. Bravo.

Check out “Story of a Rock” on Facebook.